Three Surprising Changes to the 2023 ADA Standards of Care

Let’s be honest—clinical care guidelines are pretty dry and the 2023 ADA Standards of Care is no exception. If it wasn’t so darn important to diabetes care and education I’d likely chuck it in the recycling bin on arrival. You can access the guideline in it’s entity online, or read one of many great reviews by by Hope Warshaw on DiaTribe, Dr Scott Kahan on HCP Live, or Pam Brown on DiabetesOnTheNet. While most of the revisions are minor and predictable, adding clarity or new evidence to existing recommendations, here are a few of the more surprising changes in 2023.

1. The Rise of the Community Health Worker

I am so happy to see a section added supporting the value of the community health worker. As we return to our new normalcy, many care providers have exited the field. Fueled by burn out, chronic understaffing, and the immense emotional burden of a global pandemic, there are just fewer of us around—we need an ‘all hands on deck’ approach. The updated guideline reads:

1.7 Consider the involvement of community health workers to support the management of diabetes and cardiovascular risk factors, especially in underserved communities and health care systems.

Community healthworks, or promotoras in spanish-speaking communities, are vital frontline workers that often come from the communities they serve. While their training and experience may vary, their credibility as trusted peers is undeniable.

Their work is so important that this year the Colorado Senate introduced a bipartisan bill to authorize medicaid reimbursement of community health services. It’s about time their value is recognized in the ADA Standards of Care.

2. Updated Blood Pressure and Cholesterol Goals

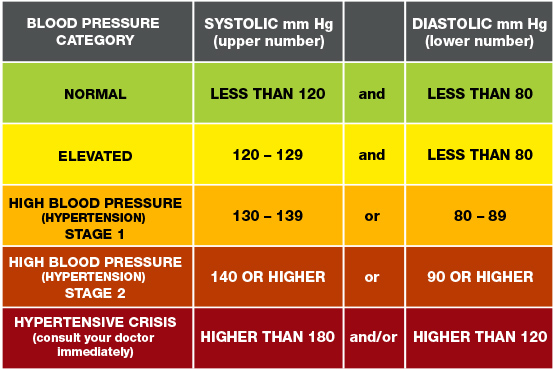

What surprises me most is the timeline for updating the blood pressure and LDL cholesterol recommendations.

Both the American Heart Association (AHA) and the American College of Cardiology (ACC) redefined hypertension back in 2017. A systolic pressure of ≥130 mmHg or a diastolic of ≥80 mgHg is enough to warrant a diagnosis. Of course, be sure to check twice to rule out errors in testing, white coat syndrome, etc. Once diagnosed, the treatment goal (with or without medication) is <130/80 mmHg. The new 2023 ADA recommendation reads as follows:

10.1 … Hypertension is defined as a systolic blood pressure ≥130 mmHg or a diastolic blood pressure ≥ 80 mmHg based on an average of ≥2 measurements obtained on ≥2 occasions.

10.4 People with diabetes and hypertension qualify for antihypertensive drug therapy when the blood pressure is persistently elevated ≥130/80 mmHg. The on-treatment target blood pressure goal is <130/80 mmHg, if it can be safely attained.

The LDL cholesterol recommendation for secondary prevention in patients with documented ASCVD was dropped to a goal of <55 mg/dL in the 2023 ADA recommendations, down from <70 mg/dL in 2022. However, this change was already recommended in 2019 by the ESC/EAS and by the AACE/ACE in their 2020 Executive Summary. The updated ADA recommendation reads as follows:

10.26 For people with diabetes and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, treatment with high-intensity statin therapy is recommended to target an LDL cholesterol reduction of ≥50% from baseline and an LDL cholesterol goal of <55 mg/dL.

For qualifying individuals already on a high intensity statin, consider additional medication therapies—ezetimibe or a PCSK9—if they are not yet meeting their LDL goal.

3. Emphasis on Greater Weight Loss

This final recommendation has me feeling torn. There is substantial evidence that links weight loss with improved insulin sensitivity, yet obesity itself does not cause the onset of T2 diabetes. T2 Diabetes can exist in any body habitus. Likewise, individuals with obesity can have near normal metabolic function.

5.12 For all people with overweight or obesity, behavioral modification to achieve and maintain a minimum weight loss of 5% is recommended… It should be noted, however, that the clinical benefits of weight loss are progressive, and more intensive weight loss goals (15%) may be appropriate to maximize benefit depending on need, feasibility, and safety.

Health status and body size are independent metrics. While a strong correlation may exist between the two to support sweeping statements in the general population, the care of our patients is individualized. Unfortunately, weight bias in healthcare is pervasive. I fear the intensification of messaging around weight loss in the diabetes community may overshadow key self-care behaviors—like exercise, healthy eating, sleep, stress reduction, etc.

I would love to hear how my colleagues practicing a Health at Every Size (HEAS) approach are navigating this updated guideline?

You May Also Like

The Value of the Diabetes Educator

June 27, 2022

CDCES and Primary Care: A Healthy Partnership

June 21, 2022